Soviet Aesthetics (I): From the Emergence of Suprematism and Constructivism to Their Influence on Western Modernism

Lenin's Passion and Breakthrough

The Establishment of the Soviet Union

In 1917, Russia stood at a pivotal juncture in history.

At the beginning of the year, a wave of worker strikes and demonstrations ignited the February Revolution. Led by Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky (1881–1970), the reformists overthrew the Tsar, bringing an end to two centuries of imperial rule and establishing the Russian Provisional Government (Вре́менное прави́тельство России).

One might have expected that the turbulence would gradually subside with the birth of this new nation. However, Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) and his Bolshevik comrades soon launched the October Revolution, toppling the Provisional Government and founding the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, abbreviated as Russian SFSR or Russian Soviet Republic).

Five years later, in 1922, Russia, along with the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and the Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, signed the Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. This accord laid the foundation for a new political entity—the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR, or CCCP in Russian).

Thus, prior to 1922, Soviet Russia did not identify itself as the Soviet Union. The Russian SFSR was merely one of the constituent republics within this emerging federation—though in practice, the core political authority and decision-making power remained firmly in its hands.

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was the first state in human history to be bound together solely by ideology. Before its establishment, the cohesion of nations had always relied on nationalism or religious identity.

Yet, the birth of the Soviet Union demonstrated that people from diverse backgrounds—regardless of ethnicity, gender, faith, or lineage—could unite under a shared belief in Marxism, setting aside past grievances to forge a common future as one collective nation.

Lenin’s Emphasis on Aesthetics and Education

Aesthetics and philosophy, as integral components of ideology, held profound significance in the Soviet vision. Under Lenin’s leadership, the Soviet government placed great emphasis on cultural education and the aesthetic refinement of its people.

From a retrospective, almost omniscient vantage point, one might argue that as the first nation bound together by ideology alone, the Soviet Union could not afford to neglect the spiritual and intellectual cultivation of its citizens. Without such foundations, the bond between the people and the state would inevitably erode, leading to a loss of faith and unity—a fate that, in hindsight, indeed came to pass.

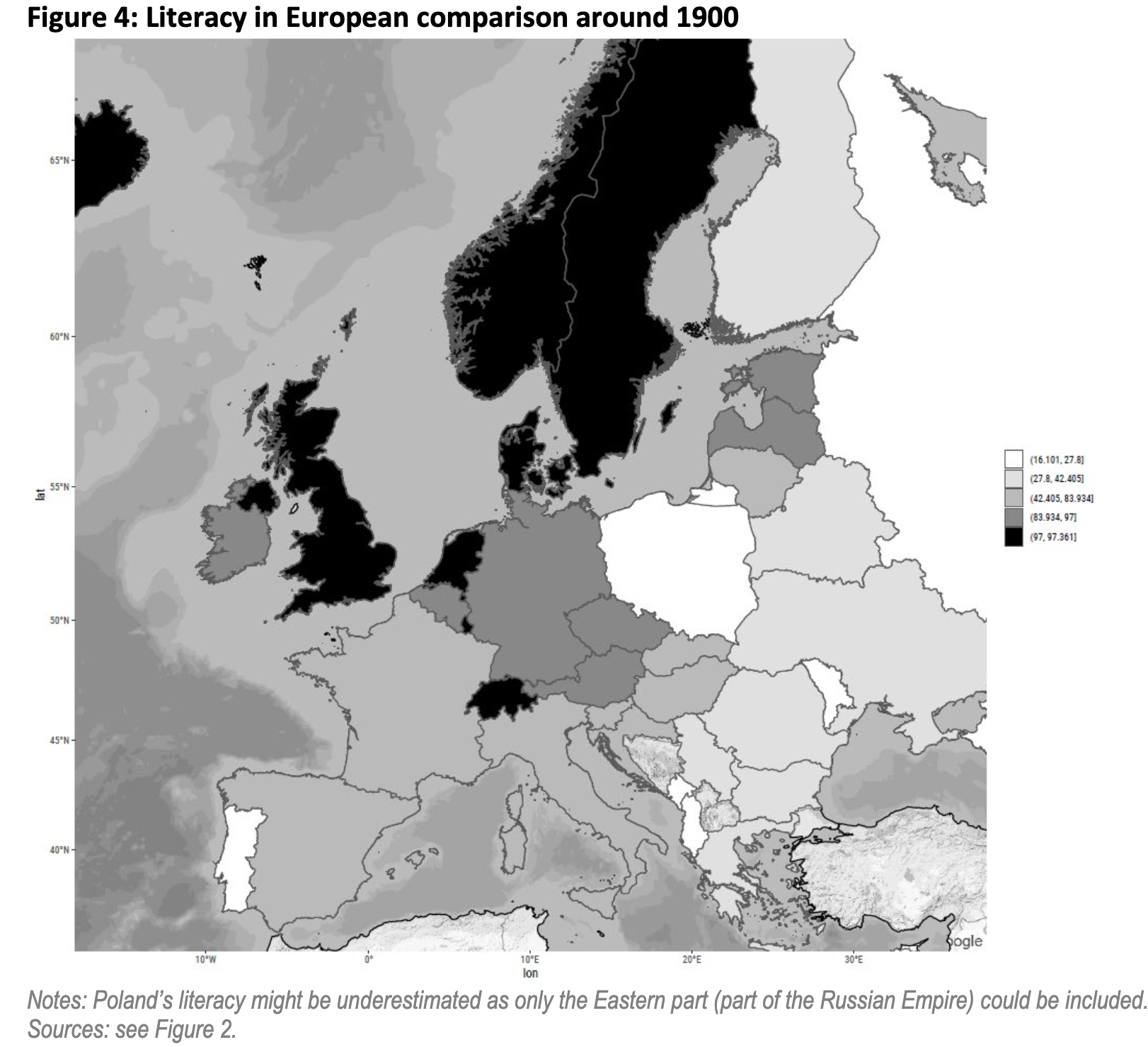

Compared to the imperialist nations of Western Europe, education in pre-revolutionary Russia was awful. Even in the twilight of the empire, the national literacy rate barely exceeded 20%, with the figures plummeting even further in rural areas and among women. By contrast, the British Empire and the Grand Duchy of Finland (1809–1917) had already surpassed a 90% literacy rate, while the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires exceeded 80%. Even in France and Italy, literacy was no lower than 40% 1.

Beyond geographical vastness and administrative challenges, Russia’s cultural and historical foundations were comparatively fragile. Before the 16th century, much of what would later become Saint Petersburg—founded by Peter the Great only in 1703—and Moscow remained largely undeveloped, covered in dense forests and swamps. Even Kyiv, under the rule of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (c. 1236–1795), was a far more vibrant center of civilization than the Grand Duchy of Moscow (1282–1547).

For the vast majority of workers and peasants, education was an unattainable privilege, an abstract notion reserved for the aristocracy and elite. Many went through life knowing only a handful of written words—often just their own names. Worse still, Russia’s involvement in World War I had decimated its intellectual class, as many of the nation’s brightest minds were sent to the frontlines, only to perish in the carnage. Emerging from the war’s devastation, the nascent Soviet state faced an urgent need to cultivate a new generation of educated youth.

Fully aware of the transformative power of culture and education, Lenin wasted no time. Mere days after the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks launched the Likbez campaign (ликвида́ция безгра́мотности, likvidatsiya bezgramotnosti—“liquidation of illiteracy”), a sweeping initiative to eradicate illiteracy and overhaul the antiquated education system of the past.

“If the ultimate goal of our Soviet state is the liberation of all humankind,” Lenin pondered, “then what kind of culture and art would be worthy of such an ideal?”

The Emergence and Development of “Russian Culture”

Before delving further into Lenin’s ideals, let us turn our attention to an earlier chapter in Russian history.

In 1453, Constantinople finally fell to the Ottoman Turks, marking the demise of the Eastern Roman Empire, which had long claimed to be the true successor of Rome.

For over a thousand years, the Greek-speaking, Orthodox Christian citizens of the Eastern Roman Empire referred to themselves as “Romans” and hailed their capital, Constantinople, as the “Second Rome.” Though the original Romans spoke Latin and adhered to Catholicism before the schism, the allure of Rome as the greatest empire in Western history was undeniable. Its legacy was an aspiration, a claim to legitimacy that transcended linguistic and doctrinal differences.

Following the fall of Constantinople, Grand Prince Ivan III Vasilyevich (1479–1533) of the Grand Duchy of Moscow sought to assert his domain’s continuity with the fallen empire. For various “pragmatic” reasons—including a politically motivated union between Eastern and Western Christian traditions—he married Sophia Palaiologina (c. 1449–1503), the niece of Constantine XI, the last Byzantine emperor. By virtue of this dynastic connection, Moscow positioned itself as the heir to Byzantium, declaring itself the “Third Rome.”

Yet, despite its claims to Roman heritage, Moscow could never truly be Rome, nor could it attain the grandeur of Roman civilization merely by adopting a prestigious title. To the Western Europeans of the Renaissance era—who had just emerged from a cultural rebirth—Moscow was nothing more than a remote and uncivilized frontier, a land still shrouded in the shadows of barbarism.

Dawn of Civilization

By the early 19th century, the currents of Romanticism had swept eastward into Russia, inspiring a new generation of poets and writers. Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin (1799–1837), hailed as the “Father of Russian Literature,” alongside Mikhail Lermontov (1814–1841), crafted works that profoundly shaped Russian literary tradition.

Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin (1833) masterfully wove together Romantic and Realist elements, portraying the stark societal conflicts of an era under autocratic rule. His characters—aristocrats and peasants alike—became iconic, stirring the intellectual and emotional currents of Russian society and, to some extent, planting the seeds of revolutionary imagination.

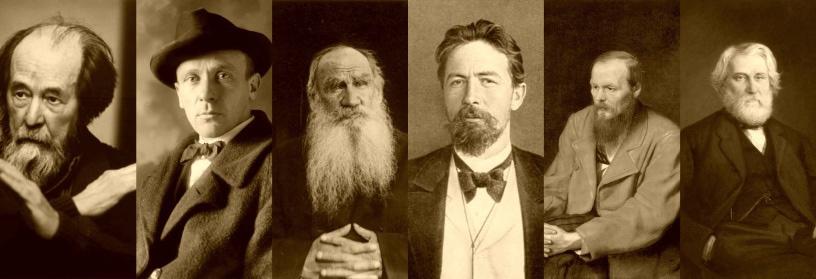

Beyond poetry, the rise of Realism in literature cemented Russia’s place as an indisputable cultural powerhouse in Europe. Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881) delivered searing psychological depth in Crime and Punishment (1866) and The Brothers Karamazov (1879–1880).

Ivan Turgenev (1818–1883) explored generational and ideological divides in Fathers and Sons (1862). Leo Tolstoy (1821–1910) etched humanity’s grand struggles into the pages of Anna Karenina (1877) and War and Peace (1869). It would not be an overstatement to say that some of the most significant novels in human literary history emerged from this era.

Prior to the 19th century, Russia had left little mark on the global literary and artistic landscape. But in the span of a single century, it underwent an unparalleled explosion of creative genius. Literary historians refer to this period as the “Golden Age of Russian Literature”—a moment when Russia finally forged a cultural identity distinctly its own, one that owed neither to Roman nor Greek heritage, but to a burgeoning Russian civilization.

As the 20th century dawned, Russia entered yet another cultural renaissance, this time centered around Symbolism, Acmeism, and Futurism—three avant-garde poetic movements that, while perhaps less dazzling than the preceding century, nonetheless marked an era of literary significance, earning it the title of the “Silver Age.”

By this time, artistic expression had expanded beyond poetry and literature. The advent of print media and cinema opened new frontiers for creativity. Artists began to question the very purpose of Realism: If photographs and film could capture reality with absolute fidelity, was there still a need for painters to render the world as it appeared? Or could art, instead, strive to depict reality through entirely new perspectives?

The Rebellion Against Realism

In response to traditional Realist aesthetics, a radical movement known as the Russian avant-garde emerged. These artists rejected the notion that art should mirror reality, instead pushing the boundaries of form, color, and abstraction. It was in this fertile experimental ground that Abstract Art was born.

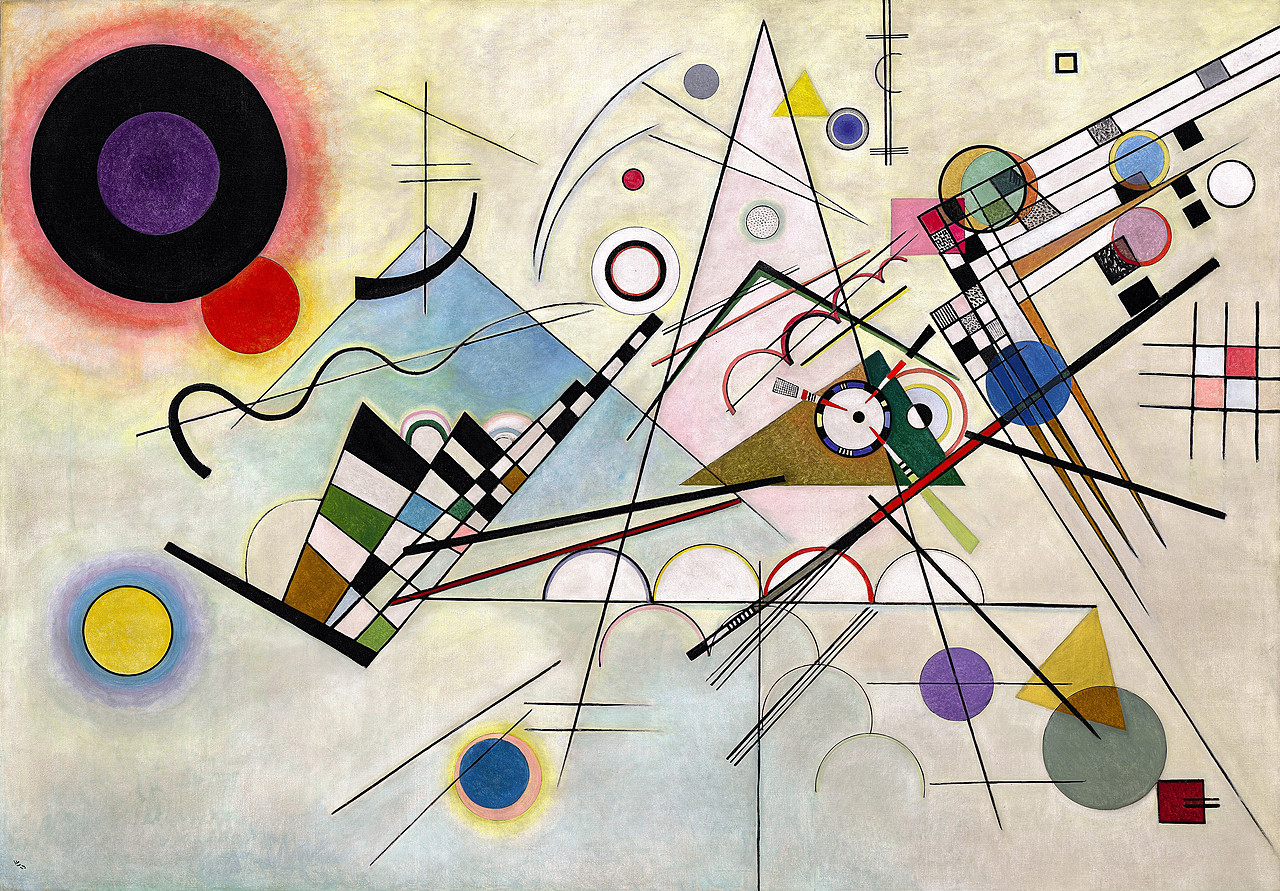

Kandinsky: Non-Objective Art

The Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) introduced the concept of non-objective art, a radical departure from traditional realism that laid the foundation for abstract art. He discarded the conventional necessity of depicting tangible subjects, arguing that art should no longer be bound by the representation of external objects—whether the human figure in a portrait or the vast expanse of a natural landscape. Instead, the essence of art should reside solely within the composition itself.

One might wonder—if an artwork is not derived from a specific reference or modeled after a visible entity, how does one create? Kandinsky placed paramount importance on the intrinsic elements of a painting: color, tone, texture, movement, and compositional balance. Through these fundamental aspects, he sought to distill beauty to its purest form.

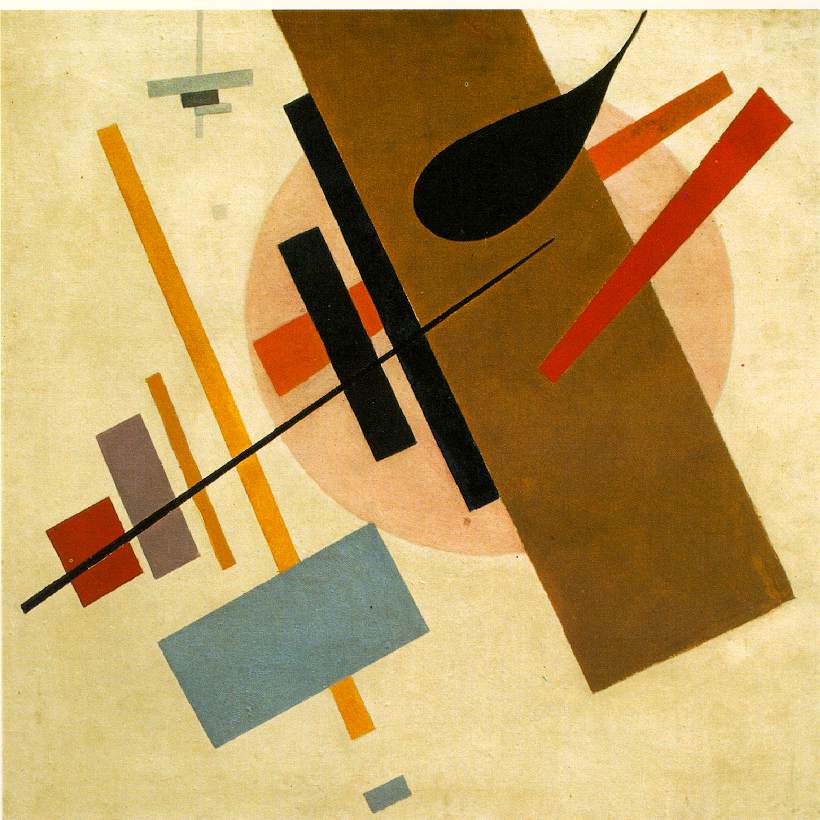

Malevich: Suprematism

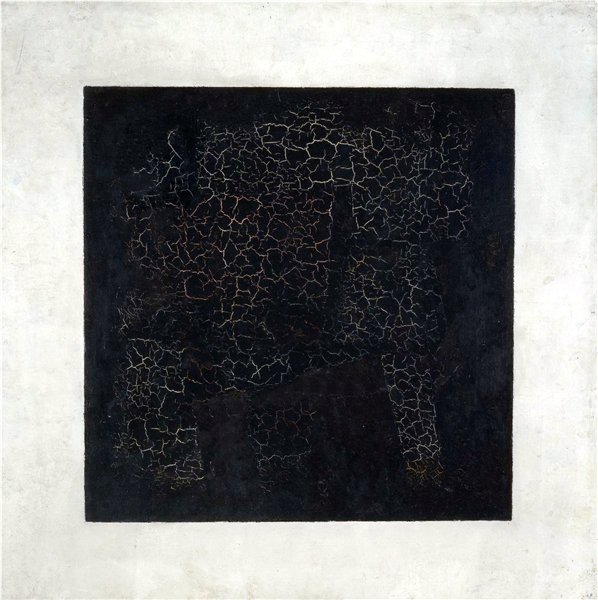

In 1915, Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) propelled abstract art to an unprecedented zenith with the unveiling of his seminal work, Black Square.

Before Malevich, artists created by bringing something into existence—starting with a blank canvas and imbuing it with meaning. Malevich, however, turned this convention on its head, advocating for the negation of both material representation and practical utility. What significance could a stark black square on a white background possibly hold? This was the challenge he posed to his audience.

The concept of a square, as a geometric form, predates human civilization and will persist long after it. Its meaning does not require interpretation—perhaps its very lack of meaning is its meaning. Malevich urged viewers to focus not on representational content but on the interplay of black and white (color), depth and flatness (tone), weight and lightness (texture), and the equilibrium between form and void.

To Malevich, this pursuit of absolute artistic purity was the pinnacle of creative expression, an aesthetic philosophy he termed Suprematism. In his manifesto From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism, he expounded on this vision:

“Under Suprematism I understand the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth.”

—Kazimir Malevich, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism

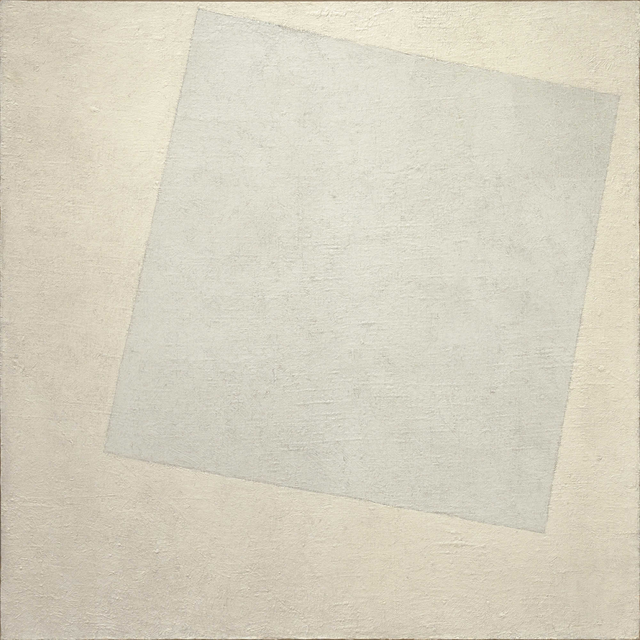

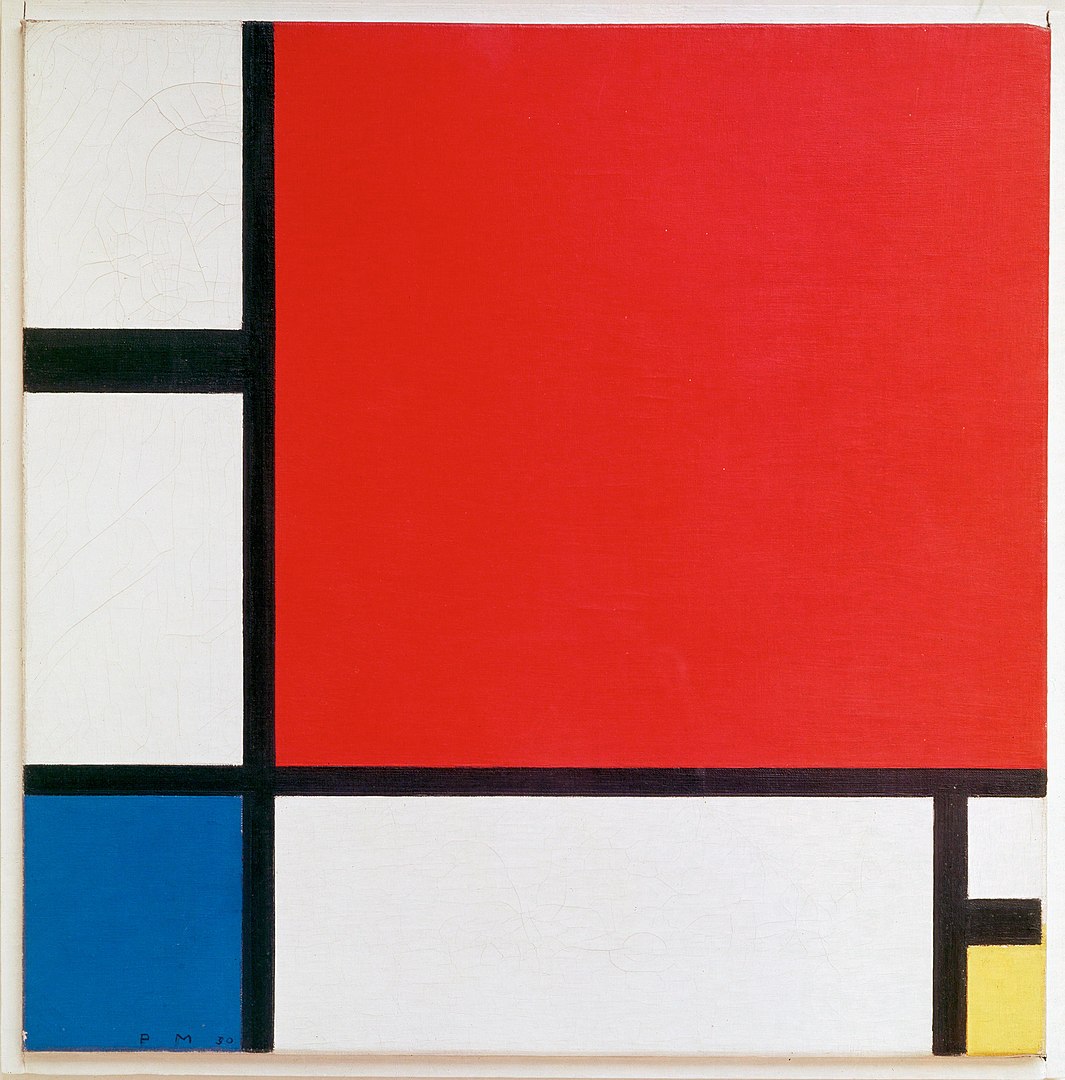

Today, Malevich and Kandinsky, alongside the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), are revered as pioneers of modern abstract art.

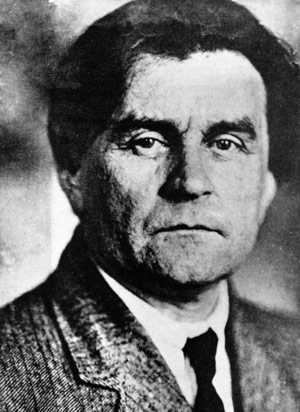

Tatlin: Constructivism

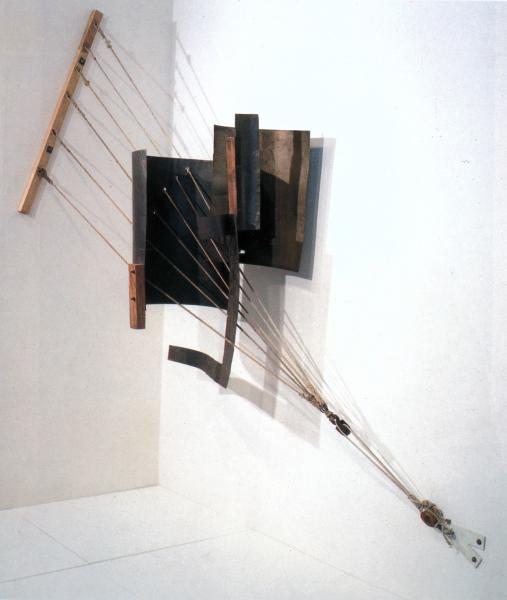

Alongside Malevich, another visionary artist, Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953), steered abstract art in a radically different direction—Constructivism. While Malevich was devoted to the planar relationships within composition, Tatlin focused on the interplay between volume and space. In his works, structure and materiality were not mere components but the very essence of the artistic expression.

Tatlin’s 1916 masterpiece, Corner Counter-Relief, marked a pivotal moment in art history. For the first time, sculpture was liberated from its traditional role as a mere imitation of human figures or objects; instead, it was elevated to an independent artistic concept.

He believed that art and technology were inseparable, using innovative materials and construction techniques to break away from conventional spatial structures, reshaping them into a new artistic language. However, Tatlin also understood that art could not remain an abstract, metaphysical pursuit—it had to serve society, imbuing practical value and purpose into everyday life.

Thus, Constructivism’s most profound influence was not on two-dimensional painting but on tangible, experiential forms—architecture, monuments, sculpture, as well as the performative realms of theater, film, and dance.

Aesthetic Debates in a New Era

Tatlin’s Constructivism and Malevich’s Suprematism emerged as two dominant branches of Russian abstract art. Though once colleagues, their ideological differences led to inevitable discord—a testament to the passion and unwavering convictions of artists.

At the heart of their dispute lay a fundamental question: Should art exist independently of practical function, or is utility merely a secondary byproduct of artistic form? Suprematism, with its anti-materialist, anti-objective philosophy, stood in stark contrast to Constructivism’s emphasis on material reality and pragmatic design.

Regardless of these artistic schisms, the avant-garde movements that emerged around the 1910s arrived at the threshold of a new world, forming a mosaic of visions that would shape the aesthetics of the future.

The Collaboration Between Politics and Art

Returning to Lenin’s vision, he recognized that art and aesthetics in past eras had either served the aristocracy or exalted religious ideals. For centuries, art had been an ornament of the upper class, with creators bound to the tastes of the elite. Outside these privileged circles, artists faced an uncertain fate—in an agrarian society, sustaining oneself through artistic creation alone was an impossibility.

However, the Soviet state sought to realize a communist utopia—one that would mobilize the global spirit and reconstruct cultural life. In this vision, artistic appreciation could no longer remain the exclusive domain of the bourgeoisie; it had to be reclaimed by the working masses, enabling laborers and farmers alike to create and engage with art.

In other words, the new artistic doctrine of the Soviet Union had to be internationalist, collectivist, and fundamentally proletarian.

The themes that had dominated past artistic traditions—mythology and religion, nationalism and historical narratives—were deemed obsolete in this new order. Even the material content of objective reality was to be stripped away, leaving only pure form. In this abstraction, free from the burdens of past conventions, lay the true aesthetic of a brighter future for all humanity.

Marx and the leaders of the October Revolution envisioned a world that was not only more just and economically secure but also more magnificent and boundless in its ideals.

Revolution and Art

As the Bolshevik regime dismantled old doctrines, it sought new artistic expressions—aligning perfectly with the avant-garde’s aspirations for a new world, a new society, a new aesthetic, and a new cultural paradigm.

With this declaration, politics and art became inextricably linked. The state emerged as art’s most formidable patron, while art, in turn, became an instrument of the revolutionary cause.

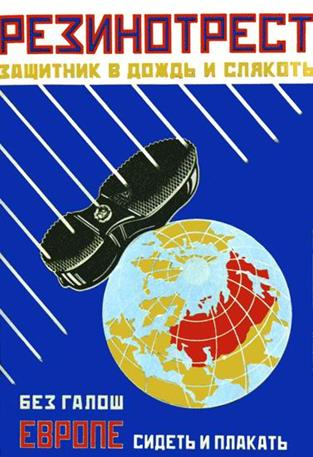

El Lissitzky: Political Propaganda Posters

Among the artists of this era, El Lissitzky (1890–1941), a student of Malevich, created one of the most iconic posters of the political-artistic collaboration: Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919).

With its simple geometric shapes, a composition optimized for stencil printing, and the seamless integration of text and imagery, the poster epitomized the new generation of propaganda design. It symbolized the Red Army of the Soviet state piercing through the anti-Bolshevik White forces in a single decisive strike.

Beyond propaganda posters, Lissitzky experimented with expanding geometric symbolism into other artistic disciplines, including theater and stage design. More radically, he sought to integrate these visual elements into daily life—applying them to walls, book covers, clothing, and even tableware.

At the time, mainstream artistic thought dismissed abstract geometric forms as too detached from human emotion. Traditionalists argued that while people could experience spiritual resonance through ancient Greek sculptures or Renaissance paintings glorifying religious themes, how could one possibly be moved by mere squares, circles, and triangles?

However, Lissitzky contended that geometry could evoke shared meaning as long as it carried a recognizable sign. In contemporary terms, this concept is known as Visual Identity (VI). Consider this: why does a simple red curve immediately evoke the image of Coca-Cola? It is because the brand has consistently reinforced this visual motif across its products, embedding it into the public consciousness over time.

This marked the first revolutionary understanding of visual identity in human history. Today, every company, every product, and even entire nations strive to shape their own VI. The market itself has validated this principle—through thoughtfully crafted geometric forms, icons, typography, layout, color schemes, and illustrations, one can evoke powerful associations that transcend mere words, exerting a far greater influence on perception and memory.

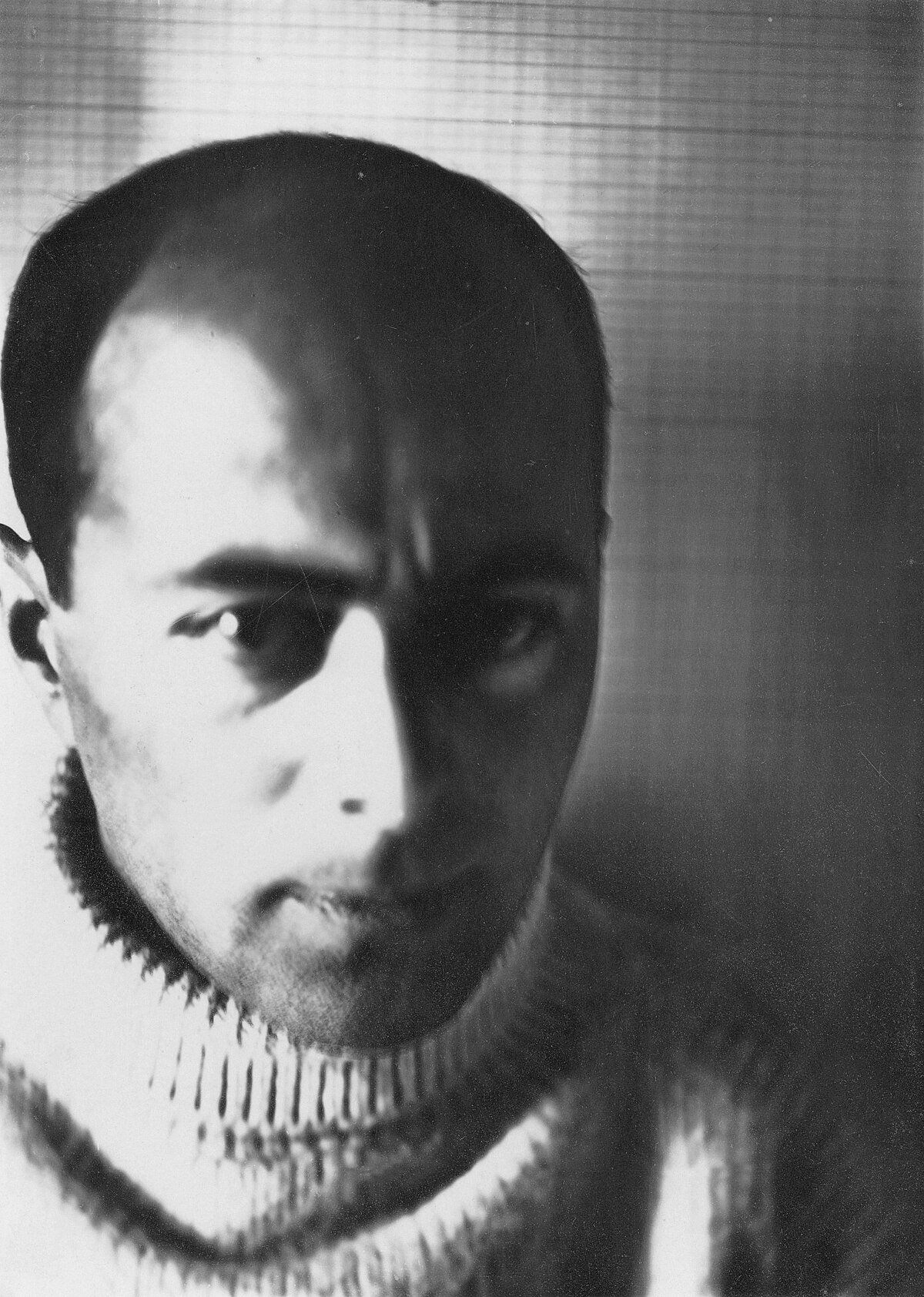

Rodchenko: Graphic Design and Photography

Another influential Constructivist master and representative of the Russian avant-garde, Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956), was profoundly inspired by Suprematism and Constructivism. His works, particularly in graphic design, would go on to shape the entire 20th century and even contemporary visual communication.

Rather than calling himself an artist, Rodchenko preferred to describe himself as a productivist, a producer of art, and he held contempt for Malevich’s lofty philosophical pursuits within art. For Rodchenko, art should serve the proletariat and align with their everyday lives. The best artists, in his view, should not be confined to galleries, museums, or studios but should be present in factories, construction sites, and workers’ quarters.

Rodchenko was a sharp critic of the traditional artistic production methods, which relied on old materials and purely handcrafted techniques. In his eyes, true art belonged to the people when it could be reproduced by machines, mass-produced, and practically applied.

From the smallest pots and pans to vehicles, furniture, and even architectural reliefs, Rodchenko steered Constructivism toward the path of “productization, practicality, and industrialization.” This, however, did not mean that these “craft objects” lacked beauty. For him, the primary value of art lay in its utility and manufacturability. Only when products met practical needs could they naturally convey aesthetic beauty during their use.

Even today, many artists still disdain the term “craft”—believing that art must be unique, highbrow, and placed in museums for public admiration. They argue that true art must emit an aura of elitism. But for the Constructivists of Rodchenko’s time, real art belonged to all humanity, not to a select elite defining its value.

From Malevich to Lissitzky, from Tatlin to Rodchenko, whether Suprematism or Constructivism, these movements reflect the search for a new aesthetic in the context of the post-Revolution Soviet Union. The artists of this era instinctively understood that only through both intellectual inquiry and practical application could they reshape society’s perception of beauty.

The Founding of VKhUTEMAS

In 1919, the Bauhaus School was established in Weimar, Germany, and the following year, in 1920, the Higher Art and Technical Studios (VKhUTEMAS) were founded in Moscow under Lenin’s directive.

Rather than being just a studio, VKhUTEMAS was more akin to a school and laboratory, exploring the nature of modern art. It also represented the Soviet Union’s journey in reimagining art education. As the center of avant-garde art and architecture movements at the time, VKhUTEMAS was instrumental in developing Constructivism, Suprematism, and Rationalism as its pillars.

Notable figures such as Malevich, Lissitzky, Tatlin, and Rodchenko all taught there, making it a hotbed for Soviet art innovation.

Although the Bauhaus in the West and VKhUTEMAS in the East were founded for different reasons, they shared similar goals: to merge traditional craftsmanship with modern industrial techniques, moving away from inefficient handmade art in favor of mass production.

At this time, the Soviet Union had only just established itself, and the optimistic environment of the revolution fostered a vibrant academic and artistic atmosphere at VKhUTEMAS. The courses offered included architecture, painting, sculpture, metallurgy, woodworking, textiles, printing, and ceramics, attracting artists from all across the Soviet Union. This collection of passionate individuals created a dynamic space where ideas collided and resonated, making VKhUTEMAS a hub for artistic reflection.

Early Soviet industrial design, characterized by simple geometric forms, clear and intuitive structural designs, bold visions of the people and the future, abstract expressions with internationalist undertones, and innovative ideas prioritizing utility, flourished at VKhUTEMAS. Teachers at VKhUTEMAS imparted lessons on how to reconstruct the world through art, while students learned how to use art to serve the realities of life.

A Shock to Europe

In 1922, VKhUTEMAS organized the first Russian art exhibition in the West, Erste Russische Kunstausstellung (The First Russian Art Exhibition) in Berlin, Germany. The exhibition showcased Constructivism, Suprematism, and Futurism, demonstrating to Western capitalist society how Eastern art had undergone a revolutionary transformation in the wake of one era’s collapse and another’s rise.

Russian avant-garde art stunned Europe at the time. The West had never imagined that Soviet art, from far-off Eastern Russia, could have achieved such a level of innovation. Many of the concepts and ideas presented were entirely new, and in some cases, unimaginable to the Western audience. Western art development had long been influenced by Classical traditions and the Renaissance, still deeply entangled with religious frameworks. Even when God was “dead,” Western art remained framed by the presupposition of God’s existence. However, Soviet art, influenced by Marxism and materialist philosophy, embraced a godless vision, unshackling itself from centuries of religious constraint, aligning instead with the future envisioned by the people.

Walter Gropius, the head of the Bauhaus School, praised the Soviet avant-garde art after seeing it, and he quickly steered the Bauhaus curriculum toward Rationalism and Constructivism. This influence was instrumental in shaping Modernism, Surrealism, Dadaism, Pop Art, and Minimalism in the West. It also influenced cinematic montage techniques (Rodchenko was the first to bring the architectural term “montage” into film photography), and introduced new methods in theater, such as Stanislavski’s System.

Influence on Architecture

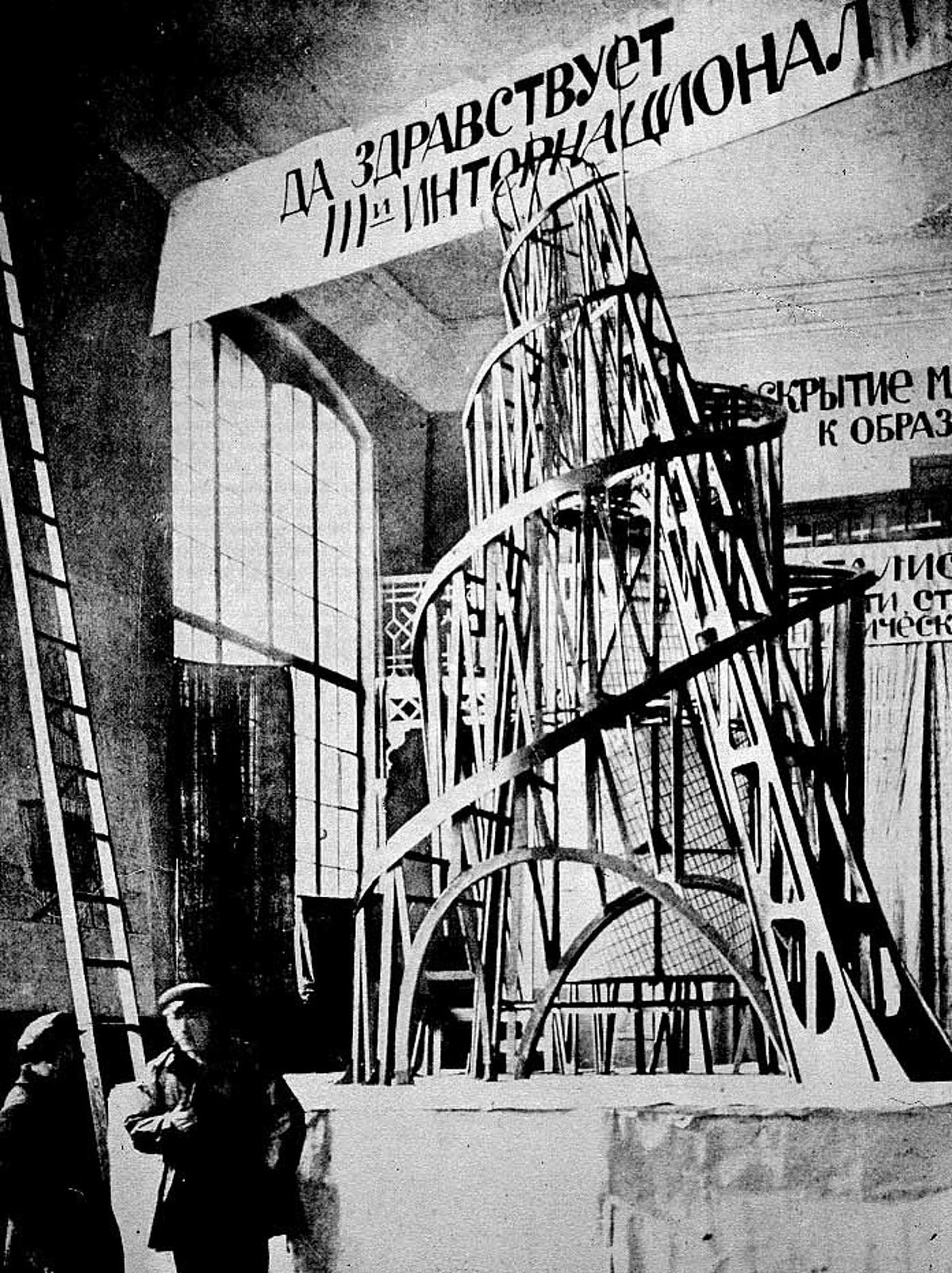

Tatlin: The Monument to the Third International

In the realm of architecture, Constructivism, with its emphasis on space and structure, naturally led to visionary designs and urban aesthetics. A prime example is the Monument to the Third International (Памятник III Коммунистического интернационала), also known as the Tatlin Tower, designed by Tatlin in 1919.

The structure resembled a spiraling shell, symbolizing humanity’s pursuit of freedom as it ascended beyond the grip of gravity. It also represented Marxist Progressivism, the belief that history is inevitably progressing toward a better future.

Hanging in the center of the tower were three geometric blocks: the bottom cube rotated once a year, the middle pyramid rotated once a month, and the top cylinder rotated once a day. The pinnacle housed a radio transmitter designed to broadcast the communist revolutionary message worldwide. It’s difficult to imagine the visionary mindset that led Tatlin to design such an avant-garde structure, but this steel-and-glass monument was clearly beloved by Lenin.

Unfortunately, due to the steel shortages in the Soviet Union at the time, this revolutionary monument remained only on paper and was never built.

Lissitzky: The Lenin Tribune

Another key design was Lissitzky’s Lenin Tribune from around 1924. He envisioned placing Lenin on a steel podium tilted at a 60-degree angle. The dynamic, unstable, yet highly energetic design of the podium reflected the passion and emotional fervor associated with communist speeches and ideologies. However, by the time Lissitzky finished his design, Lenin had already passed away, and the project was never realized.

ASNOVA and OSA

In the VKhUTEMAS, the architects split into two factions. One was the ASNOVA (Association of Modern Architects), founded in 1923 by Nikolai A. Ladovsky, which advocated for a rationalist approach to architecture. The other was the OSA (Organization of Contemporary Architects), founded in 1925 by Moisei Ginzburg, which emphasized function and aimed to improve society through architecture.

ASNOVA: Association of Modern Architects

ASNOVA became known for its bold imagination for the future, such as Lissitzky’s Horizontal Skyscrapers. Historically, all human architecture has been vertical, like the legendary Tower of Babel, which symbolizes humanity’s ambition to reach the heavens. However, Lissitzky argued that horizontal developments in architecture were more natural.

The idea of a horizontal skyscraper did not become a reality until 50 years later in 1975, when Georgian architect Georgiy Chakhava designed the first horizontal skyscraper for the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic’s Ministry of Highway Construction and Management. Today, this building is home to the Bank of Georgia.

Another notable figure in ASNOVA was Konstantin Melnikov (1890-1974). For the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris, Melnikov designed the Soviet Pavilion, a rectangular wooden structure divided by a staircase. Half of the facade was made of glass, while the other half was open to the outside. The two-story building employed modern wooden construction techniques.

The 1925 Paris Exposition was one of the most important art events post-World War I and marked the beginning of modernist and internationalist architecture. Another highlight of the Exposition was the Pavillon de l’Esprit nouveau by modernist master Le Corbusier (1887–1965). The modular residential structure shared similar aesthetic qualities with the Soviet Pavilion, further connecting the ideologies of East and West.

The historical irony is that, despite the differing political and cultural contexts, both the Eastern and Western visions of modern art converged during this period.

OSA: Organization of Contemporary Architects

Unlike ASNOVA’s bold visions for futuristic architecture, OSA focused on developing housing. At the time, many workers and peasants in the Soviet Union couldn’t afford homes, so the priority was to create modular, standardized social housing. They introduced the concept of the “Social Condenser”, which aimed to break away from the isolated individualism of old estates and rural life. By designing shared public spaces within communities, they sought to dissolve social classes and provide more equal community spaces for people.

In 1928, Moisei Ginzburg began working on the Narkomfin Building project in Moscow. Unlike private housing models driven by capitalist ideals, the Narkomfin apartments drastically reduced private spaces, transferring many functions to communal areas. These included shared kitchens (yes, no private unit had its own kitchen—residents had to cook in public spaces), laundry rooms, kindergartens, libraries, and other facilities, all integrated into the residents’ daily routines. This approach was similar to the communal facilities seen in modern buildings in Taiwan, but instead of restricting communal spaces to the ground or top floors, it emphasized overlapping and intermingling private and public spaces, promoting a collective way of life aimed at achieving social cohesion.

Le Corbusier, deeply inspired by the Narkomfin Building, later incorporated similar ideas into his Unité d’habitation housing project. A prime example of this influence can be seen in his Marseille Housing Unit, which mirrors the Narkomfin design in its vertical functional spaces distributed across various floors. The entire building acts like a small vertical city, where residents can meet all their daily needs without leaving the building, moving between floors to access different facilities.

This architectural approach not only influenced the modernist movement but also reshaped the concept of urban living by integrating the collective spirit into daily life.

Epilogue

Art is born from the reflection upon past lives, the passion for the present, and the longing for a future yet to come.

In the decades surrounding the October Revolution, Russian avant-garde artists ventured beyond the realms of flat art into architecture, giving birth to ideas and concepts that remain strikingly progressive even by today’s standards. Their reflections on the past and aspirations for the future were inextricably linked to the boundless optimism of a world that embraced radical transformation.

Moreover, Lenin’s emphasis on aesthetics and education provided fertile ground for these artists to flourish. Though Lenin himself might not have fully grasped the intricacies of their work, he did not impede the dissemination of their revolutionary ideas. “This awakening, this activity that will create a new art and culture in Soviet Russia,” Lenin proclaimed, “is good, very good. The rapid pace of this development is self-evident, and it is beneficial.”

Alas, the death of the great Lenin in 1924 threw Soviet leadership into turmoil once more. Upon Joseph Stalin’s (Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin, 1878-1953) assumption of power as General Secretary of the Soviet Union, the winds of freedom quickly dissipated. Socialist Realism became the sole official aesthetic of the Soviet state, and the suprematism and constructivism of the Lenin era were relegated to the status of unofficial ideologies, with many artists’ works subjected to harsh repression and censorship.

In 1930, the Vkhutemas institution was shut down by Stalin’s orders, and it was divided into multiple smaller schools. Perhaps by fate, the Bauhaus, too, was ordered to close by Nazi Germany in 1933. For Stalin, who was raised in the clergy, his aesthetic sensibilities were firmly rooted in classicism and classical traditions. Unlike abstractism, which sought to unify human thought through geometric forms, Stalin wished to demonstrate that the “great Socialist Soviet Union” could surpass the West in mastering classical ideals.

In 1932, the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party issued the decree “On the Reorganization of Literary and Artistic Associations”, disbanding all artistic collectives and condemning abstractism and Western modernism as too closely aligned (which, given the mutual influence over the past several decades, was not surprising). These ideologies were denounced as “bourgeois, degenerate ways of life,” thereby ending the artistic diversity of the Lenin era. That same year, Stalin’s commission for a design contest for the Soviet Palace of Soviets selected a classical design by Boris M. Iofan, V. Gelfreich, and V. Shchuko, symbolizing the marginalization of constructivism in the Soviet Union.

Thus, Soviet aesthetics shifted from abstractism to align more closely with the New Renaissance, Neoclassicism, and Imperial styles—an entirely new chapter in the cultural narrative.

-

Schooling, literacy and numeracy in 19th century Europe: long-term development and hurdles to efficient schooling.(2022). Link: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000383171 ↩︎